Tullia’s mother, Giulia Campana from Ferrara, was considered an exceptional beauty. It should then come as no surprise that the attractive courtesan won the heart of Cardinal Ludovic d’Aragon. She was his long-time partner and the mother of his daughter. When in 1519, their patron died, both Tullia and her mother left Rome. Giulia continued to be successful in Siena, while also sparing no money for the education of her daughter, who exhibited a lively mind since a very young age, along with an excellent memory and immaculate language with a Tuscan accent (especially valued among the elites). Several years later they returned to Rome and settled near the Tor Sanguigna maintaining a house with numerous servants. As time passed, with Giulia’s charms no longer what they once were, it was time to make a decision concerning the fate of young Tullia. It seemed obvious that she would continue along her mother’s path. Another solution was going to the convent or getting married in exchange for an enormous dowry, as this was the only way to erase the blemish upon the honor of a man who was willing to marry the daughter of a courtesan. Giulia made her decision.

When she was sixteen years old, Tullia was already recognized as a courtesan, but the circle of her adorers was limited to youths. It was not until Sacco di Roma (1527), meaning the months-long siege of the city, that her career truly took off. She was adored no longer simply by the young but also by mature men, including intellectuals who succumbed to the woman's exceptional aura and her sarcastic sense of humor. How do we know? For example, from the texts of a certain Giovanni Battista Giraldi, who wrote with disgust about meetings at Tullia’s home, where guests danced as played the lute in exchange for a promise of corporeal pleasures which they were ultimately refused. Not everyone was pleased with this sort of manipulation, while the men who disliked Tullia were left seething as she did not offer charm, grace, submissiveness, and sweetness, but rather irony, jests, and eloquent conversation. Her attractiveness was a result of the qualities of her intellect and her method of seduction, which worked wonders on either refined or youthful minds.

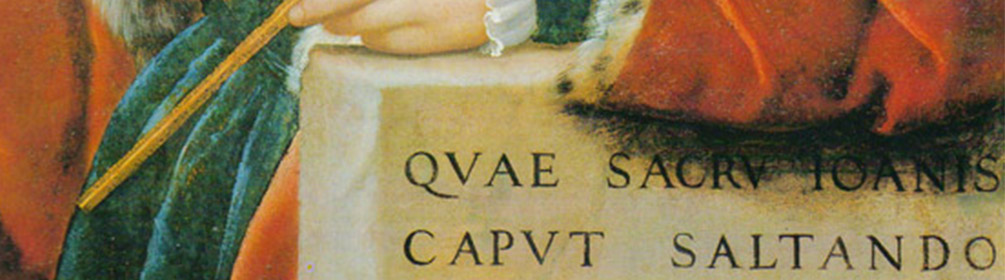

There are no certain images of Tullia – however, we have access to some paintings, which may be her portraits. They confirm, that she was not what one would call a classical Italian beauty – an early matured and well-built woman. She was tall, which for men at that time detracted from her attractiveness. Her hair, despite being light-colored, was straight. She had beautiful eyes, but also a long nose. Yet despite all of that, she was always surrounded by a crowd of adoring men, who wrote sonnets in her praise, and were even ready to give up their own lives to save her honor. Among her admirers, there were people such as the banker Filippo Strozzi, or aristocrats such as Ippolito de 'Medici. The home of the "intellectual courtesan", also known as "the courtesan of academics", was a meeting place for the elites to discuss poetry, music, but also to play music together (e.g. during the Holy Week). Tullia was the perfect example of the idea of courtliness, described by Castiglione in his Book of the Courtier, an idea which – especially in Rome – could not develop among women of noble birth. They were locked away at home and did not take part in social life.

Pietro Aretino – the greatest expert when it comes to the community of the Roman courtesans, the author of the extremely popular dialogue entitled The Lives of Courtesans (1534, 1536) neither valued nor liked Tullia. She did not fit the mold of kindly ladies of easy virtue because of her, as he put it “excessively calculating mind”. He also did not hesitate to call her “the most depraved of all whores". In his famous work, he himself noted that being a courtesan provides a woman with great opportunities – under the condition that she does not fall in love. Toying with men's feelings, lying to them in various ways is quite beneficial – as he claimed. For it must be said that at that time the profession of a courtesan had many negative aspects, but also one very attractive benefit – namely freedom!

Unfortunately, Tullia’s rules for her adorers lifted the bar extremely high. When rumors spread around the city, that this refined queen of the literary salons gave herself willingly to a perverted German for an enormous sum of money her status fell. Young men felt betrayed while she was insulted at every step. These insults proved so cumbersome, that Tullia along with her mother decided to depart for Venice – a city that was particularly friendly towards courtesans. Such women praised in poems were its main tourist attraction. Once again Tullia acquired a great number of adulators, who also applauded her eloquence and literary interests. It is in Venice that she met the renowned poet Bernardo Tasso – her great, albeit brief love. However, in 1537 she left Venice to go to Ferrara, where she once again became famous for her literary salon, impeccable manners, and her abilities in reciting and singing. She emanated wealth, while her jewelry was admired and praised. Her lofty behavior attracted adorers willing to pay her bills, fulfill her every whim, bring her valuables, and throw feasts in her honor. In this way, she attracted numerous poets and writers, whom she readily befriended, aware of the power of the written word, also as an advertising tool. Among these was the poet Girolamo Muzio, whose beautiful verses immortalized her allure and grace for centuries. At that time Tullia also wrote sonnets for Muzio.

Since it was necessary to frequently exchange a circle of admirers, a few years later Tullia went to Siena. And it is here that she officially changed her lifestyle. She married (1543) to a rather unknown man from Ferrara, who was probably part of a group of her previous lovers. He was only there to ensure her married status and that was all. Yet despite her marriage, Tullia was twice accused that as a courtesan she did not dress properly and did not live in the district designated for women of this profession. She was found innocent, but nevertheless, she decided to leave the town. This time she went to Florence. She was no longer young – approaching her fortieth birthday, but the city known for its high artistic culture became special for her – for it was here that she decided to prove her literary talents. This time she was the one who wanted to get into the good graces of a famous Florentine poet and philosopher Benedetto Varchi, whom she chose to be her master and patron. Thanks to him she could count on a successful literary start, but he was also a source of great knowledge. She showered him with numerous poems, praising him, as was customary at that time. She exalted his talents, but also complained of his insensitivity which did not allow him „to fill her heart with the greatest knowledge”. And as it turned out, Varchi, known for his weakness towards women, at first reluctant due to his tainted reputation (he had been recently imprisoned for raping a nine-year-old girl), not only fell in love with Tullia, which resulted in the exchange of love poems but also occupied himself with correcting her sonnets. He aided her in improving her texts, even when the flames of love no longer burned as brightly. And it is he, whom Tullia can thank for her growing fame, as a poetess in Florence, fame on which she wanted to build a new career – not as a courtesan, but as a poetess. This of course did not mean that she could live off of poetry, although she probably had hoped this would be the case. Soon she was able to establish a veritable literary salon, where many skilled writers and philosophers, as well as members of the noble families, gathered. Tullia fell in love with a twenty-four-year-old nobleman, Piero Mannelli. And probably this event would not bear any great significance, had it not been for the fact that this burning love, or more appropriately the jealousy resulting from the indifference sometimes exhibited by her lover, led Tullia into a state of doubt and pain – from which – as was noted by Georgina Masson (Courtesans of the Italian Renaissance) – she could only free herself through poetry. And thus the author of rather average praise hymns, directed towards people who could prove useful to her, transformed into a veritable bard of love with all of its chasms of doubt and sadness. Her sonnets also emanated with fear of the future and old age. This should come as no surprise as generally the life of an elderly courtesan was tragic indeed. Although Tullia was able to save some money this could not be enough for her and her son, whom she gave birth to in the meantime, and about whom we learn only from her will. In the spring of 1547, Tullia suffered the greatest humiliation: she – a poetess, the founder of a literary salon known throughout Florence – was called to appear in front of the court to explain why she appears publicly in silk robes and jewelry, and does not wear a yellow veil or shawl with a broad, yellow stripe. The archives in Florence still contain correspondence on the subject. In the end, Tullia was not required to wear a yellow head covering. As the court argued – this was due to her abilities and talents in the field of poetry and philosophy! In this rather unusual way, Tullia was elevated as a poet. She quickly began working, creating a booklet of poems dedicated to the Grand Duke and his wife, in which she collected her own works as well as those dedicated to the ducal couple by the great poets of those times.

In 1548 Tullia returned to Rome. At that time she was around fifty years old. She settled in the city center, at via dei Prefetti; the annual rent amounted to forty scudos, which is a testimony to the high material status of the tenant. Where did her profits come from? Most likely from her younger sister Penelope, at that time a thirteen-year-old girl, with a beauty that was noticed not only by Rome's writers. However, the girl died a year after arriving in the Eternal City, while one of the poets dedicated a poem to her entitled The Little Courtesan. We do not know who was Penelope's father, but we are also unsure about the mother – it is quite possible, that she was not the sister, but rather the daughter of Tullia. Soon after Tullia’s mother, Giulia also passed away. Our heroine was left alone. At that time she no longer inhabited her expensive apartment, but an inn at the Piazza in Piscinula on the Trastevere. She was often ill and financially supported the Church with the hope of receiving a proper burial, while in 1556 she wrote her will. With great care, she listed all her clothes, which were to be inherited by the wife of the innkeeper, she also wrote down all the fabrics, curtains, and lingerie. In addition, she had new clothes made for her doctor, who (probably) cared for her during the last months of her illness. Her jewelry and books were sold, along with the furniture and everything else that was left behind. Most of her wealth was given over to her underage son, left under the care of the cook of cardinal Cornaro.

She was buried, as had been the case with many other wealthy courtesans, in the Church of Sant’Agostino next to her mother and sister.

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska

BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108

or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !